Huguenin Family History

HUGUENIN FAMILY HISTORY

by Edward Ulric Huguenin

The first appearance of the name Huguenin in France goes back to the year 1292. The Census Parisiorum refers, at that date, to the presence in Paris of a so-called Huguenin le Bourguignon, this name suggesting a Burgundian origin. We can find also, in Burgundy, a certain Hughes Bourgogne, called Huguenin, born in 1260 and dead in 1288. In fact the name HUGUENIN comes probably from the slopes of the Jura mountains where it is still alive and well referenced, particularly in the swiss areas of Neuchatel and La-Chaux-de-Fonds as well as on the French part of the mountains. It is probably from this French part of the so-called “Franche-Comte” that some Huguenin families could have emigrated during the 13th and the 15th centuries to settle in Switzerland, attracted by the freedoms conceded by the landlords of Neuchatel and Valanges to help them to settle and develop the mountain land.

In Switzerland, a large Huguenin family comes from Le-Locle, little town in the higher part of the Neuchatel district and specialized in clock making. The known ancestor, named Outhenyn Chiez Heuguenin, was a free-burgher and lived here at the end of the 15th century. Counting his descendants still living in Switzerland, those emigrated to the States or to Australia, and others, they are still about 8500 who bear the name, either simple or compound. They are numerous in the United States and also in Holland.

In France, according to the INSEE data, we can find about 3613 persons bearing this name, setting it at the 2158th rank of the most borne french names. This name is frequent in the eastern part of France, particularly in regions such as Lorraine, Champagne-Ardennes, Burgundy and Franche-Comte. Somebodies try to do a connection between the name “Huguenin” and the calling of Huguenot given in 1550 by the Genevian catholics to the Calvinists. But, the name was living long before this calling and so, the connection is without any foundation. The name derives probably from Hughes, itself coming from Hug , an old germanic name meaning “spirit” or “thought”. In France and in Switzerland, the name is present under different forms or variations: Hugounin, Hugounenq, Huguenet, Hugonin, Hugueny, frequently completed by a prefix or a suffix such in Petithuguenin or Huguenin-Virchaux… These double names are very typical of the Neuchatel swiss district and of the french Franche-Comte.

Near the end of the 19th century, a Parisian branch of the Huguenin family, by the marriage of Edouard Huguenin, son of Bonaventure Alexis Huguenin, from the french Champagne, was allied with the family Drieu, from Saint-Lo in Normandy. This family is from an old Norman ascendance, one of its known ancestor being a man called Drieu Le Normand, born in 1045, and fellow of William the Conqueror in 1066 during the conquest of England. He was still living in 1086 and his descendants in England, by his son Walter Drieu, shall bear the successive names of Drui (1200), Drury (1300) then Drewry after the emigration in North America of Robert Drury, in 1635. This name of Drieu could come from an old medieval French word meaning “love-token”. The Drury were, in medieval England, a very prominent family. They counted 18 Knights, 5 Sheriffs of the Norfolk and Suffolk County and 4 Earl Knights. Some members of the family were councellors of the Kings of England and among the richest families of the Kingdom.

Roseland Plantation Avenue

Roseland Plantaton near Coosawhatchie, South Carolina was purchased in about 1782 by David Huguenin, a descendant of Outhenyn Chiez Huguenin, after it was confiscated from a Tory baron named John Rose. Roseland has been home to descendants of David until the present day. The oak trees in the picture are near the family cemetery, which dates back to the 1790s.

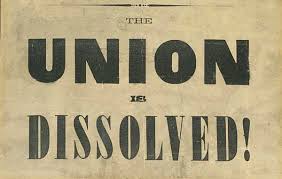

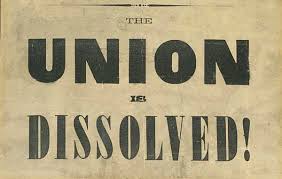

A description of Roseland written in late 1864 by Dr. Henry Marcy, a surgeon with the Union army, appears in the next column. In 1865 the mansions were burned by troops of the 144th New York Volunteers under the command of Gen.William T. Sherman. In a twist of fate, the sergeant in charge of burning Roseland was another Huguenin, a descendant of David Huguenin’s father.

Over the years, Roseland grew to about 25,000 acres and then gradually was sold to other owners. However, it is now expanding again as parts are being repurchased by David L. Huguenin, a descendant of the original owner. Roseland was the childhood home of David L., his brothers Edward and Julius, and their sister Kathy.

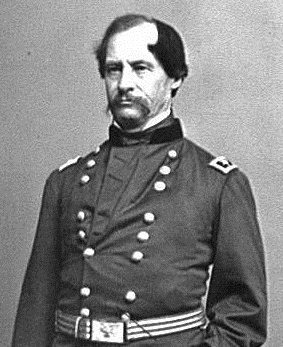

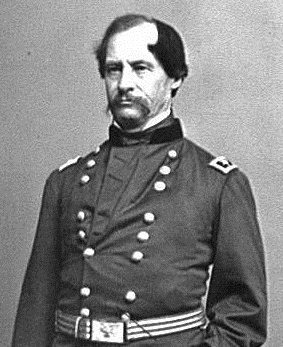

Dr. Henry Orlando Marcy, 1837-1924

35th Regt. U.S.C.T.

Diary of a Surgeon, U.S. Army, 1864-1899

Sunday, Dec. 4, 1864

At noon we halted near the plantations of the Huguenin’s about a mile from Roseland, the name of the mansion’s house. In company of several others I went down. I think it one of the most lovely spots I have ever seen. Pen would fail to do it justice. It is near the Coosawhatchie River situated on high ground, in a splendid grove of live oaks of a centuries growth. Outhouses and all at a distance bear the look of a country village. Every outhouse was nicely whitewashed. The grounds were beautifully laid and splendidly kept. The mansion was huge and eloquently furnished. We found a detachment of the Navy here raising mischief. They were drinking and destroying property most shamefully. The slaves had been all removed. I obtained a few books. Among others a copy of the Confederate States Regulations which showed that one of the Huguenins was a Capt & a QM. in service. From a colored man I learned that the father had died a few years previous and left 9 plantations and several hundred slaves to two sons and two daughters. The property lay so near the coast they did not dare to trust the slaves to work here and have moved them into the interior. Only a few old men and woman had been left to care for the whole tract. The sons are both in service. We returned at evening without loss. Spent the day more happily there in camp, yet should have preferred, if the exigency of the service would have permitted, to make our movements other than on Sunday. We were trying to find where the Bee’s Creek Battery is located. We shelled where we suffered it lay and our gunboats have been firing all day with their heavy guns, but they have remained silent. ‘Tis said to be a strong work.

Beck, Ann (Huguenin), b. 25 Mar 1773, d. 12 Mar 1836, Wife of Rev. John Beck

Beck, Jane Amanda, d. 16 Oct 1817, daughter of Rev. John & Mrs. Ann (Huguenin) Beck

Beck, John David, d. 18 Sep 1826, 21y 7m

Beck, John, Rev., b. 19 Aug 1755, d. 19 May 1818, 62y 9m

Bryan, Thomas S., d. 29 Sep 1859, Only child of ?.J. & M.S. Bryan, 5y

Colcock, Sara Rebecca, (Huguenin), d. 1 Jul 1829, Wife of W.F.Colcock, 21y

Huguenin, Abraham, b. 7 Aug 1778, d. 11 Apr 1846, 67y

Huguenin, Abram, Capt., b. 5 Oct 1838, d. 11 Feb 1885

Huguenin, Anna Marie, (Gillison), b. 14 Jul 1785, d. 25 Jan 1854, Wife of Abraham Huguenin

Huguenin, Beulah Irene, (Corbett), b. 18 Jul 1886, d. 10 Sep 1970, Wife of Edward Percy Huguenin, Sr.

Huguenin, Cornelius M., Col., b. 23 Feb 1817, d. 31 Jul 1856, 40y

Huguenin, Edward Percy, Jr., b. 22 Jul 1918, d. 21 2 1982

Huguenin, Edward Percy, Sr., b. 4 9 1885, d. 27 10 1966

Huguenin, Eliza Louisianna, (Morrell), b. 29 Mar 1815, d. 7 Feb 1861, wife of Julius G. Huguenin

Huguenin, Frances Martha (Rice), b. 24 Apr 1918, d. 28 Mar 2000, Wife of Edward Percy Huguenin, Jr.

Huguenin, Julia Adelaide, d. 18 Jul 1849, Second daughter of Cornelius M. & Adelaide Huguenin, 7y 3m 4d

Huguenin, Julia Theodore, d. 26 Aug 1838, Only daughter of Julius & Theodora Huguenin, 10y

Huguenin, Julius Abram, b. 23 Oct 1925, d. 29 Apr 1954

Huguenin, Julius Gillison, b. 19 Dec 1806, d. 16 Aug 1862

Huguenin, Lawrence Augustus, b. 12 Jul 1814, d. 14 Jul 1816, Infant son of Abraham & Anna Huguenin

Huguenin, Mary Ella (Stroud), b. 23 Feb 1937, d. 18 Mar 1982, Wife of Edward Percy Huguenin, Jr.

Huguenin, Theodore, b. 31 Dec 1812, d. 31 Dec 1812, Infant son of Abraham & Anna Huguenin

Huguenin, Theordora Octavia (Gaillard), b. 5 10 1806, d. 5 11 1831, Wife of Julius Huguenin, youngest daughter of Theodore & Martha Gaillard, 25y 1m

Huguenin, Thomas Edgar, b. 19 Jan 1811, d. 8 Jun 1812, Infant son of Abraham & Anna Huguenin, 16m 20d

Huguenin, William John, b. 27 Oct 1791, d. 1 Nov 1818, 27y 5d

To learn more about the Huguenin Family please visit the link: